Context

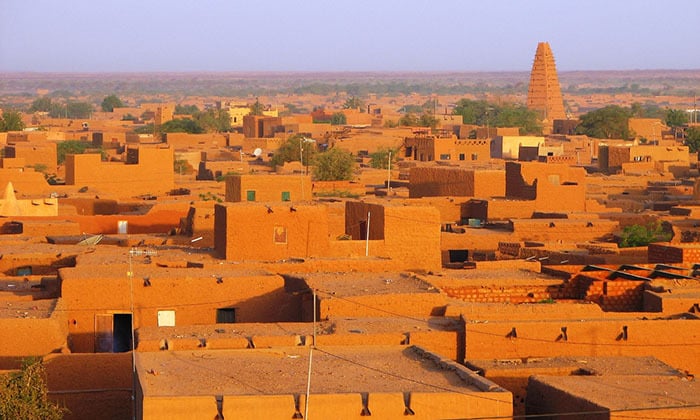

Located in the heart of the Sahel, Niger is one of the poorest countries in the world, although its subsoil is rich in resources. Its geographical position gives it the status of a ‘migratory crossroads’, making Niger a country of origin, transit and destination for migratory movements. In addition to the difficulties associated with poverty and socio-economic development, Niger, like its neighbouring countries, is going through a major security crisis. The country has been the scene of numerous terrorist attacks, especially since 2011. Unlike most of its neighbours in the region, Niger has continued until recently to rely on collaboration with foreign forces, notably France, for its security strategy. This proximity is being contested by an ever-growing section of the population. The resentment of the population and its mistrust of this foreign interventionism were mobilised by the military junta to justify its coup d’état in July 2023.

The coup came after Niger had elected Mohamed Bazoum, a candidate close to outgoing President Mahamadou Issoufou, as its new president in 2021, in what was seen as the country’s first democratic transition of power, despite opposition protests alleging fraud. The new president promised to tackle corruption and said he wanted to relaunch dialogue with civil society.

After two years, the hopes of a good number of citizens had still not been answered. The price of living, the security situation, the closure and deterioration of a large number of schools and the restriction of public freedoms were major concerns for civil society and rights holders.

Civil liberties

A number of new laws and legislation adopted in recent years were already deemed to be prejudicial to the rights and freedoms of the people of Niger. The almost systematic refusal of demonstrations, the law on terrorism and other new legislation such as the 2015 law against the smuggling of migrants, the 2019 law on cybercrime and the 2020 law on the interception of electronic communications have been denounced by human rights organisations because of the serious attacks on freedom of expression, movement and privacy.

Justice and human rights

In 2021, 130 lawyers were registered with Niger’s only Bar Association, located in Niamey. There are no law firms outside the capital. In 2021, the Ministry of Justice’s budget represented only 0.49% of the total State budget.

In Niger, access to justice is far from guaranteed for the population. So-called “modern” justice remains generally inaccessible to the population. There are very few courts and tribunals in the country, even though 85% of the population lives in rural areas. Local people still rely heavily on so-called “traditional” justice to settle their disputes.

Modern” law and “traditional” justice therefore coexist in Niger. And even though Nigerien law recognises the jurisdiction of ‘traditional’ justice to settle some conflicts, the two systems still struggle to coordinate effectively. Geographical, security, economic, social and cultural barriers continue to impede access to justice. The justice sector suffers from a structural and chronic lack of funding, and the necessary reforms to the judicial system are slow in coming.

Detention

Prison overcrowding is endemic in the country’s main prisons, infrastructure is dilapidated and access to basic healthcare and sufficient healthy food is not guaranteed. 70% of the prison population in Niger is awaiting trial.

ASF’s intervention strategy

ASF wants to support the agents of change in Niger in order to promote the rule of law and guarantee the security of citizens. These conditions must be met to enable local populations to contribute actively to the socio-economic development of their country. To achieve this, ASF gives priority to improving access to justice and creating opportunities for dialogue and consultation between institutions and those subject to the law.