ASF joins the Open Society Foundation, APCOF, PALU, and ACJR in a campaign to promote the decriminalisation and declassification of minor offences. “Vagrancy”, “disorderly behaviour” or “idleness” remain valid grounds for arresting and imprisoning individuals, contributing to the endemic overcrowding of prisons throughout the world. Particularly affecting people in vulnerable situations, these laws and their application are both arbitrary and discriminatory.

In many countries on the African continent, such offences date back to colonial times. But while these laws have been repealed in the former colonial powers, they remain in force in many African states.

By providing a criminal response to socio-economic issues, vulnerable populations are further marginalised. Maintaining these minor offences in the penal code therefore fuels a vicious circle. In many countries, the criminalisation of minor offences is one of the main sources of prison overcrowding. Decriminalising these offences and ending the detention of people who are not a danger to public order is the only way out in the long term.

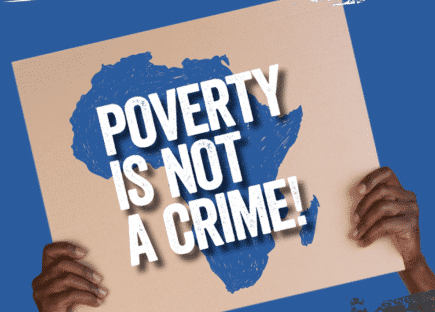

Within the framework of the Poverty is Not a Crime campaign, several organisations have united to decriminalise these minor offences. Advocacy actions are being organised at national and regional level, mobilising ASF’s teams and partners.

Following an interpellation launched at the initiative of the Pan-African Lawyers Union (PALU), the African Court of Human and Peoples’ Rights ruled unanimously on December 4th 2020 in favour of the decriminalisation of minor offences. It declared these laws and regulations incompatible with the African Charter, the Children’s Charter and the Maputo Protocol. It is in accordance with this opinion that it ordered the States concerned to review, repeal and, if necessary, amend these laws and regulations.

The criminalisation of minor offences is incompatible with the constitutional principle of equality before the law and non-discrimination. It has a considerable impact on the poor, vulnerable people and women and infringes on many of their freedoms, including freedom of movement and freedom of expression.

Following the positive decision of the African Court, ASF joins civil society organisations to call for the repeal of such offences and all forms of unjustified repression.

(more…)