Category: Monitoring Covid-19

-

Indonesia: 5 years supporting access to justice

In 2017, ASF launched its activities in Indonesia with two local partners. Together, we worked to increase access to both formal and informal justice mechanisms for marginalized and groups in vulnerable situations through improved community-level, evidence based service delivery. A special focus was put on training and supporting paralegals to help them assist local populations…

-

A dire need to integrate human rights in the Covid-19 crisis management

As authorities initially downplayed the gravity of the Covid-19 health crisis, a sense of astonishment prevailed throughout the world at the unprecedented nature and scale of the measures that were later taken. More than half of the world’s population has found itself locked down, with varying economic, social, physical and mental consequences on individuals depending…

-

The health crisis in Belgium: A breeding ground for indirect discrimination?

Avocats Sans Frontières publishes a study on the indirectly discriminatory impact of Belgian emergency policies on certain categories of the population, particularly vulnerable ones. The analysis, carried out as part of the project ‘Covid-19 Monitoring and Rule of Law’, relies on observation activities, as well as a set of interviews conducted by ASF in June…

-

Indonesia: A cacophonic legal response to the Covid-19 pandemic to the expense of human rights

Indonesia has been particularly impacted by Covid-19. According to official data, Indonesia ranks second within South East Asia in terms of positive cases ; fifth in terms of mortality rate. 20,5% of Covid-19 cases were located in the capital city, Jakarta. This blogpost focuses on the legal response adopted in the first phase of the…

-

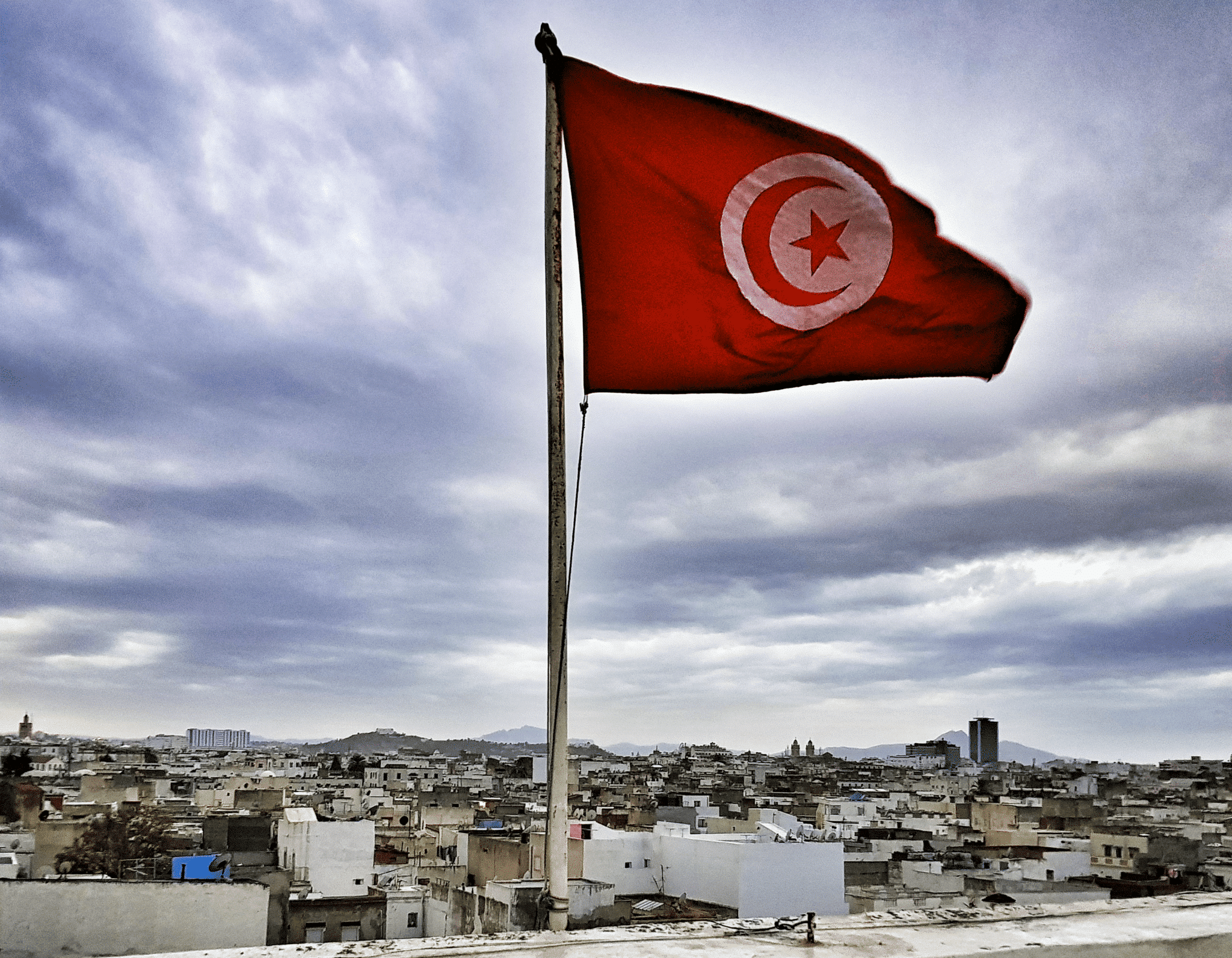

The Tunisian response to the Covid-19 pandemic – When the state of exception overlaps with the state of emergency

As the Covid-19 pandemic entered a peak phase in China and was becoming more and more threatening in Europe, Tunisia very quickly deployed a preventative response, conscious of its health system’s weakness to contain such a crisis. The first measures were thus put in place on 26 January, with the installation of thermal cameras and,…

-

Uganda’s de facto state of emergency to address the Covid-19 pandemic

Oeganda, gesterkt door zijn recente ervaring met het aanpakken van het ebolavirus, heeft een masterplan ontwikkeld om de verspreiding van COVID-19 tegen te gaan. Preventieve maatregelen werden vanaf 18 maart genomen, zelfs voordat het eerste geval van besmetting geregistreerd werd in het land. Terwijl het eerste geval geregistreerd werd op 22 maart, was het gezondheidspersoneel…