Category: News

-

Legal clinics to support access to justice during pandemic

Throughout the world, the pandemic has pushed people further away from access to justice. In Morocco, ASF has been relying for several years on legal clinics, set up in universities, to promote access to justice, particularly for people in vulnerable situations. Under the supervision of teachers and legal professionals, students provide legal services to the…

-

Between walls – Mohamed Ramsis Ayari “The real bête noir in prison is overcrowding”

(Nederlands) In het kader van het project “Alternative”, gefinancierd door de Europese Unie en uitgevoerd door ASF en ATL MST SIDA, streeft de Association des Juristes de Sfax naar de modernisering van het penitentiaire en strafrechtelijke systeem in Tunesië. Door middel van verschillende pleitbezorgings- en bewustmakingsactiviteiten met magistraten en gevangenispersoneel in Sfax werkt de vereniging…

-

Press release – NGOs call out to Perenco: end the opacity to tackle the multinational’s impunity

In a letter made public today, Sherpa, Friends of the Earth France and Avocats sans Frontières call the oil company Perenco S.A out. Our associations denounce the opacity of Perenco group’s organization and operation, as well as the absence of any information on the way the French company takes into account the social and environmental…

-

Reparation to victims of international crimes in the Democratic Republic of Congo, a major challenge in the fight against impunity

ASF has been active in the fight against impunity and the field of international justice for over 15 years in the DRC. During that time, the organization has witnessed great progress but regrets that current mechanisms are still not up to the challenges at stake.

-

Djugu killings: Significant evolution of Congolese jurisprudence on reparations

The Djugu 2 trial came to an end on 1 April 2021. It concluded with 21 defendants being sentenced to life imprisonment for crimes against humanity by murder, arson, destruction, pillaging and persecution, and 11 defendants being acquitted. The 219 civil parties were also granted most of their claims for reparations, both individual and collective,…

-

Patrick Henry : “In a growing number of countries, the very notion of human rights is being challenged.”

Avocats Sans Frontières is about to celebrate its 30th anniversary. The Journal des Tribunaux sat for an interview with Patrick Henry, the newly elected ASF’s president, to address the organisation’s history and its special relationship with Belgian lawyers and bar associations.

-

Between walls – Omar Ben Amor (Art Acquis) : “Access to culture to every detainee at any time”

Discover the work done by the association Art Acquis with prisoners in Tunisia. With its Perspectives project, supported by ASF and ATL MST SIDA Bureau National, the organisation uses art as therapy. Through the activities offered, it seeks to help prisoners express themselves better about their experience, to occupy themselves constructively during their incarceration and…

-

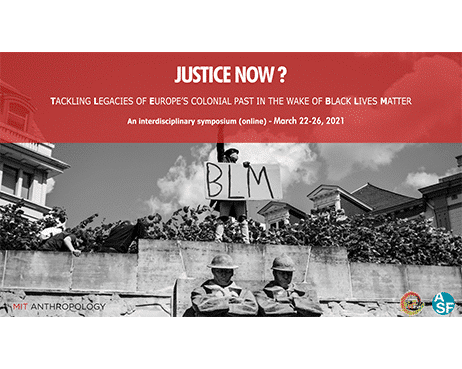

JUSTICE NOW ? Tackling legacies of Europe’s colonial past in the wake of Black Lives Matter

ASF co-organizes an interdisciplinary conference with the Anthropology Department at MIT, and the European Network against Racism fom the 22nd to the 26th of March 2021. Over the course of five half-days, scholars, activists, and policy makers from Africa, Europe and North America will address issues related to Europe’s colonial heritage and the global demands…

-

Between walls – Walid Bouchmila (Horizon d’Enfance) : “When you make a project in prison, you really have to think of everyone”.

Within the “Projet Alternative”, implemented by Avocats Sans Frontières and ATL MST SIDA, Horizon d’Enfance sets up cultural activities at the Gabès prison, training courses for prison staff and qualifying training courses (plumbing, plastering, culinary arts and pastry making) for prisoners. The latter also benefit from training in entrepreneurship, support in setting up micro-projects and…