Category: Transitional justice

-

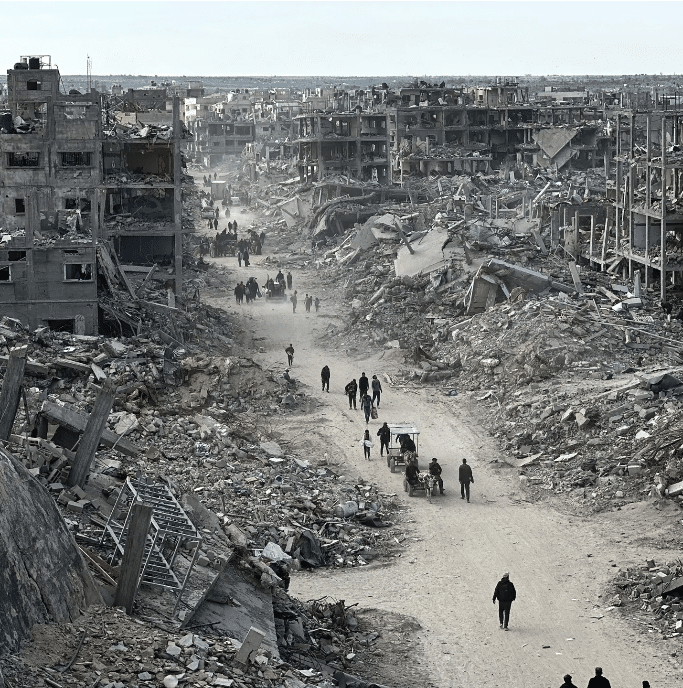

International justice and the universality of human rights in question in the face of double standards and the dehumanisation of Palestinians

Since 7 October 2023, the crisis in Gaza has rekindled major geopolitical tensions while exposing systemic flaws in international law and the system of global governance. In this context, ASF reaffirms the need to guarantee the protection of civilians and respect for international humanitarian law. Beyond the concrete violations committed by the Israeli government and…

-

The US sanctions against the International Criminal Court curtails the ability of victims globally to obtain justice

On 6 February 2025, an Executive Order was adopted by US President Donald Trump imposing sanctions on the International Criminal Court (ICC). The imposition of sanctions on the ICC constitutes an unjustified resort to coercive measures that infringe on the Court’s judicial independence and could severely affect its ability to fulfil its mandate to combat…

-

We oppose the US sanctions against the International Criminal Court (ICC)

The Coalition for the International Criminal Court and more than 120 of its member non-governmental organisations and coalitions from around the globe strongly oppose efforts by the United States of America (US) to impose sanctions related to the International Criminal Court (ICC) and urge ICC member states to defend the ICC, its officials, and those…

-

Pursuing an integrated approach to Transitional Justice and Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration (DDR) in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Since the emergence of both fields of practice in the 1990s, Transitional Justice (TJ) and Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration (DDR) policies, projects and programmes have operated simultaneously in many (post-conflict) settings. However, most often TJ and DDR have been developed and implemented in complete separation from one another. This is despite the recognition that both…

-

Democratic Republic of Congo – Fight against impunity: The needs and expectations of victims of serious human rights violations as a compass

ASF has been supporting victims of international crimes in the Democratic Republic of Congo since 2004. In close collaboration with the Congolese authorities, UN agencies and international partners, ASF documents international crimes and offers legal and judicial support to victims before, during and after the trial.

-

Transitional Justice and (Post)Colonial Justice

In collaboration with the Leuven Institute of Criminology, ASF published a series of articles examining the challenges and questions raised by the recent rise of processes to address the historical injustices of slavery and colonialism, particularly in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement.

-

ExPEERience Talk #9 – Using digital to support victims and promote justice: the Back-up project of We are NOT Weapons of War

For this 9th ExPEERience Talk, we are delighted to welcome Céline Bardet, founder of the organisation We are NOT Weapons of War (WWOW) whose mandate is to fight sexual violence in conflicts, in particular against rape as a weapon of war. She will talk about the importance, in the face of these issues, of support…

-

Thomas Kwoyelo trial: Prosecution moves close to wind-up presenting its witness

The Trial of Thomas Kwoyelo resumed on 17th April 2023 and is scheduled to run up to the end of the month at the International Crimes Division of the High Court (ICD) sitting at Gulu High Court in Gulu City, Northern Uganda.

-

Transitional Justice & Historical Redress: A special series on historical injustices stemming from slavery and colonialism

Over the next few weeks, ASF will be publishing a series of articles examining the challenges and questions raised by the recent rise of processes implemented to address the historical injustices of slavery and colonialism, particularly in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement. This special series is a collaboration between Avocats Sans Frontières…

-

Consolidating discussions on transitional justice: the debate on access to land rights in the Acholi sub-region

In recent years, numerous and continued conflicts about land use and ownership in the Acholi subregion have led to strong debate among the Ugandan population. But the discussions surrounding this issue have too often omitted to include it in the broader debate around transitional justice.