Country: Uganda

-

-

-

-

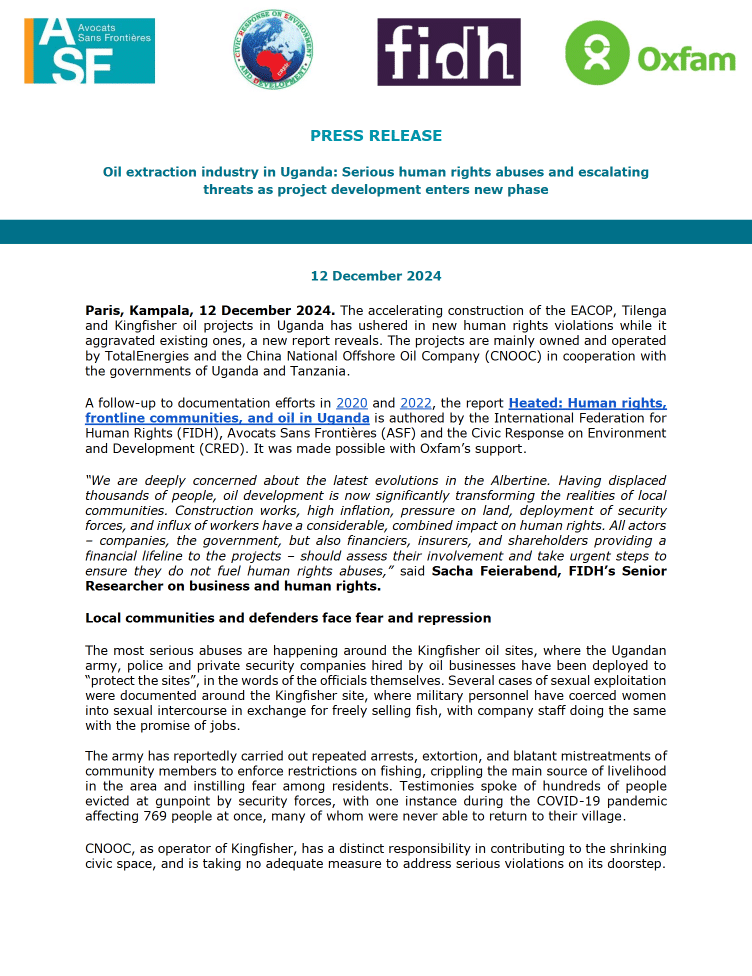

The oil sector in Uganda: serious human rights abuses and escalating threats as project development enters new phase

In collaboration with the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) and Civic Response on Environment and Development (CRED), ASF has published a report on human rights violations committed by major oil companies in Uganda and the repression of human rights defenders by the state.

-

-

-

The Justice ExPEERience network keeps growing: evolution and new features

Justice ExPEERience celebrated its 3rd anniversary this summer! To mark the occasion, the network’s coordination team is proud to present the Justice ExPEERience annual report.

-

-