Category: Victim’s rights

-

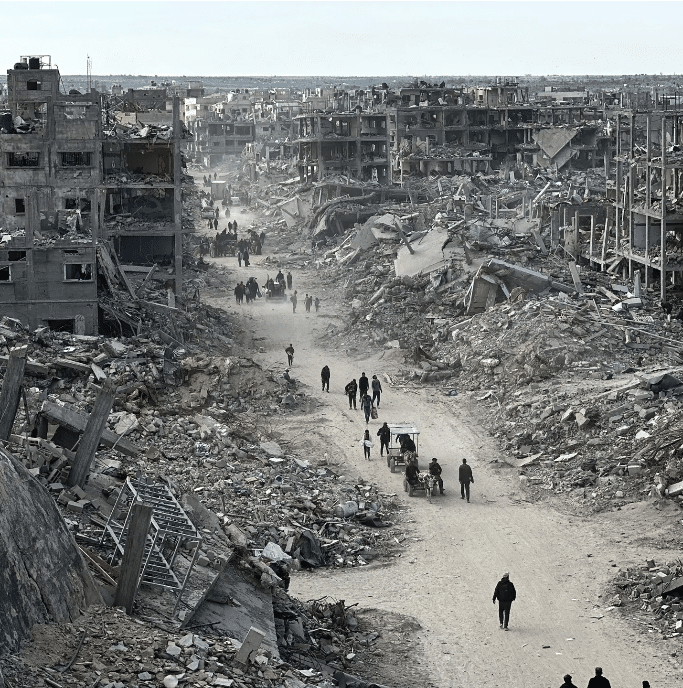

International justice and the universality of human rights in question in the face of double standards and the dehumanisation of Palestinians

Since 7 October 2023, the crisis in Gaza has rekindled major geopolitical tensions while exposing systemic flaws in international law and the system of global governance. In this context, ASF reaffirms the need to guarantee the protection of civilians and respect for international humanitarian law. Beyond the concrete violations committed by the Israeli government and…

-

We oppose the US sanctions against the International Criminal Court (ICC)

The Coalition for the International Criminal Court and more than 120 of its member non-governmental organisations and coalitions from around the globe strongly oppose efforts by the United States of America (US) to impose sanctions related to the International Criminal Court (ICC) and urge ICC member states to defend the ICC, its officials, and those…

-

Pursuing an integrated approach to Transitional Justice and Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration (DDR) in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Since the emergence of both fields of practice in the 1990s, Transitional Justice (TJ) and Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration (DDR) policies, projects and programmes have operated simultaneously in many (post-conflict) settings. However, most often TJ and DDR have been developed and implemented in complete separation from one another. This is despite the recognition that both…

-

Democratic Republic of Congo – Fight against impunity: The needs and expectations of victims of serious human rights violations as a compass

ASF has been supporting victims of international crimes in the Democratic Republic of Congo since 2004. In close collaboration with the Congolese authorities, UN agencies and international partners, ASF documents international crimes and offers legal and judicial support to victims before, during and after the trial.

-

Tunisia: People in migration threatened by the rise of discriminatory rhetoric and policies

Because of its geographical position and proximity to the European coast, Tunisia has long been considered a major transit country for sub-Saharan migrants. However, heightened security measures and the militarization of the European Union’s borders, as well as border outsourcing policies, have meant that Tunisia has become a country of settlement for many people in…

-

ExPEERience Talk #14 – Protecting Indigenous Rights to Land and Natural Resources: perspectives on the carbon market in Kenya

This talk aims to shed light on the complex relationship between carbon markets and indigenous rights in Kenya, with possible lessons to be learned for other countries in the region, and beyond. By incorporating perspectives from academic researchers and representatives of indigenous communities, the event seeks to contribute to ongoing discussions on environmental justice and…

-

Ituri: Impact of the state of siege on criminal justice

En mai 2021, l’État congolais a décrété un régime exceptionnel d’état de siège dans la province de l’Ituri pour tenter de mettre fin à plus de trois décennies de violence dans la région. L’ituri est le théâtre de guerres, d’insurrections et de violents conflits armés sur fond de crise de légitimité politique, de crise identitaire…

-

ExPEERience Talk #9 – Using digital to support victims and promote justice: the Back-up project of We are NOT Weapons of War

For this 9th ExPEERience Talk, we are delighted to welcome Céline Bardet, founder of the organisation We are NOT Weapons of War (WWOW) whose mandate is to fight sexual violence in conflicts, in particular against rape as a weapon of war. She will talk about the importance, in the face of these issues, of support…

-

Thomas Kwoyelo trial: Prosecution moves close to wind-up presenting its witness

The Trial of Thomas Kwoyelo resumed on 17th April 2023 and is scheduled to run up to the end of the month at the International Crimes Division of the High Court (ICD) sitting at Gulu High Court in Gulu City, Northern Uganda.